Sharing her advice on building an inclusive curriculum, Group Leader Lisa said, "Culturally relevant thinking and pedagogy is allowing students to bring their experience into the classroom." At Brightspark, the world is our classroom, and she inspired us to consider how diverse communities influenced some of our favorite cities over centuries of migration, struggle, and progress.

Keep reading to discover the impact of ethnic and religious populations on five student tour destinations.

Chicago

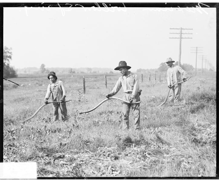

Starting in 1910, the Mexican Revolution "was a complex and bloody conflict" causing "economic, social, and political displacements." Following opportunities in agriculture and industry, Mexican migrants made their way to Chicago and worked in railyards, stockyards, and steel factories. Along with southern Blacks moving to the city during the Great Migration, their cheap labor was used to bust strikes, leading to reverberating tensions with European workers.

Starting in 1910, the Mexican Revolution "was a complex and bloody conflict" causing "economic, social, and political displacements." Following opportunities in agriculture and industry, Mexican migrants made their way to Chicago and worked in railyards, stockyards, and steel factories. Along with southern Blacks moving to the city during the Great Migration, their cheap labor was used to bust strikes, leading to reverberating tensions with European workers.

Immigration from many European countries was restricted in the early 20th century, but no limits were in place for Mexico. While "housing was substandard," Mexican migrants faced fewer housing regulations than African Americans. Once in the city, they formed "residential enclaves" in South and West side neighborhoods.

By the 1930s, the city's Mexican community had a resilient social network featuring its own newspapers, factories, restaurants and markets, sports teams, and mutual benefit societies. As the Great Depression took its toll, many returned home. Chicago's Mexican population fell by almost half until migration trends rose after World War II.

Today, you can experience Mexican history and culture in Chicago's Pilsen neighborhood, where you can enjoy authentic cuisine, tour "colorful and distinct murals," and visit the National Museum of Mexican Art.

Explore more of Chicago's ethnic neighborhoods at the Chinese-American Museum, the DuSable Museum of African American History, the National Hellenic Museum, the Polish Museum of America, and the National Museum of Puerto Rican Art & Culture.

Los Angeles

Of the 44 Mexican settlers who founded Los Angeles in 1781, "26 of them were of African descent." The impact of these "forgotten founders" was felt from Mexico throughout the American West. By the mid-1800s, Pío de Jesús Pico, a mulato of mixed race with African ancestry, had served in multiple government leadership roles.

After the Civil War, emancipated Blacks moved to Los Angeles and established a community rooted in the church. At the turn of the century, the city saw "a 'quiet' migration of southern African Americans with middleclass outlooks and ambitions." With Central Avenue as their focal point, they built on the progress of previous arrivals founding social clubs, newspapers, and other businesses.

The city saw an influx of poorer Blacks in the 1930s. Propelled by World War II and defense manufacturing, the African American population in Los Angeles ballooned, "outpacing that of all major northern and western cities from 1940 to 1970, jumping from 63,700 to 763,000 people.”

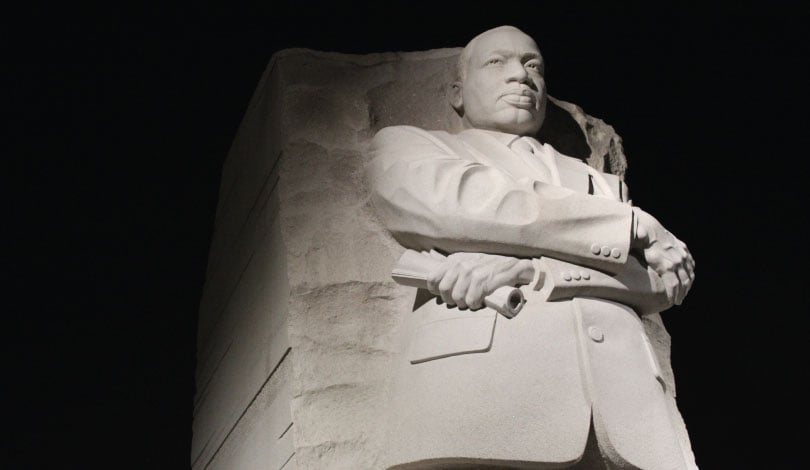

In 1965, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, a traffic stop by a White cop in the predominantly-Black Watts neighborhood quickly escalated, unleashing six days of gunfire, arrests, fires, and racist attacks. The Watts Rebellion left 34 dead, questions unanswered, and a "new era of DIY activism" on the horizon.

Over "successive streams of migration," African Americans influenced art, architecture, business, and politics in Los Angeles. Discover their history and impact at the California African American Museum.

Explore more ethnic diversity in Los Angeles at the Pacific Asia Museum, LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes, the Italian American Museum, and the Southwest Museum of the American Indian.

New York

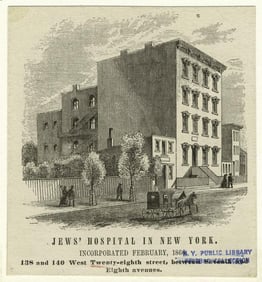

Since Sephardic Jews arrived in New Amsterdam in 1654, the community has been a reflection of the city's diversity. In the 1800s, most Jews immigrated from Central Europe and spoke German. Tensions with "the old Sephardic elite" divided the local congregation, and the city's first Ashkenazi synagogue was founded in 1824.

The most prominent Jewish neighborhoods were in Manhattan's Lower East Side, Crown Heights and Brownsville in Brooklyn, and the South Bronx. This diverse and sprawling footprint helped transform New York City: they set up public housing, established hospitals, formed political organizations, fueled industry, and contributed to the arts.

The most prominent Jewish neighborhoods were in Manhattan's Lower East Side, Crown Heights and Brownsville in Brooklyn, and the South Bronx. This diverse and sprawling footprint helped transform New York City: they set up public housing, established hospitals, formed political organizations, fueled industry, and contributed to the arts.

By 1920, the Jewish population had swelled to 1.5 million residents drawn to the freedom of the city: "There was a lot of struggle and conflict within the Jewish community about what being Jewish meant. But in New York, they could be anything that they wanted to be."

Despite their strong community ties, anti-Semitism took hold as Jim Crow laws and legal discrimination spread throughout the country. This sentiment grew after World War I, leading to restrictive immigration rules that "severely cut new Jewish settlement" in the US.

After World War II, many New York City Jews moved from to the suburbs and other states, spreading their impact from coast to coast. Learn more at the Tenement Museum and the Center for Jewish History.

Explore more of New York City's "sheer diversity" at the Museum of Chinese in America, El Museo del Barrio, the Ukrainian Museum, the National Museum of the American Indian, and the Museum of African Art.

San Francisco

The promise of gold in the region lured a growing Chinese diaspora in the mid-1800s. Realizing that "the gold mountain was an illusion," laborers left the mines to join the garment industry, work the land, and lay down railway track. Chinese immigrants "were instrumental in building the transportation infrastructure that helped fuel the westward expansion of the United States."

Excluded from many trades due to "language barriers and discrimination," Chinese transplants carved out their own opportunities by starting their own businesses. California tried to pass discriminatory laws to sabotage their progress. And in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act barred entry from China and kept those already in the US from gaining citizenship—many families irreparably split in two with an ocean between them.

Excluded from many trades due to "language barriers and discrimination," Chinese transplants carved out their own opportunities by starting their own businesses. California tried to pass discriminatory laws to sabotage their progress. And in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act barred entry from China and kept those already in the US from gaining citizenship—many families irreparably split in two with an ocean between them.

Stunting the development of Chinese communities across the country, the restrictions weren't lifted until 1943. In the interim, immigrants built self-sufficient, isolated neighborhoods. San Francisco's Chinatown is the largest and oldest such enclave in North America.

The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and ensuing fires decimated the neighborhood, leaving many dead. The loss of birth and immigration records created a loophole for Chinese immigrants to claim US citizenship and "send for their families."

In 1965, the Immigration and Naturalization Act brought a new wave of Chinese immigrants to San Francisco, revitalizing a rebuilt Chinatown. The 30-block district is now a vibrant tourist destination. Learn more at the Chinese Historical Society of America Museum.

Explore more of the Bay Area's ethnic diversity at the Museum of Russian Culture, the Japanese American Museum of San Jose, the Portuguese Historical Museum, the Mexican Museum, and the Museo Italo Americano.

Toronto

Muslims have called Canada home since before the country's founding. Some may have been West Africans enslaved before British abolition in 1833, or runaway slaves from the US. Seeking opportunities in agriculture, Islamic immigrants from various countries settled in the central provinces. The Klondike Gold Rush and the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, both in the late 1800s, grew the population and shifted its presence northwest. From a census tally of 13 in 1871, Canada was home to almost 800 Muslims by 1911.

As numbers shrank over the following decades due to racism and dwindling economic opportunities, Canadian Muslims began to congregate in urban centers—and their cultural influence grew. The country's first mosque opened in the 1930s, McGill University established its Islamic Studies program in 1952, and the Muslim Society of Toronto opened its Islamic Center in 1961.

Thanks to the post-war baby boom and an open-door immigration policy, the congregation grew exponentially, creating strains between "older, liberal members and more conservative arrivals." Accommodating the growing and divergent ranks, Toronto's Jami Mosque opened at the site of an old church. Splintering of the community fueled mosque construction across the city and suburbs. In the 1970s, political unrest in Africa and the Middle East brought even more diverse Muslims into the city.

Thanks to the post-war baby boom and an open-door immigration policy, the congregation grew exponentially, creating strains between "older, liberal members and more conservative arrivals." Accommodating the growing and divergent ranks, Toronto's Jami Mosque opened at the site of an old church. Splintering of the community fueled mosque construction across the city and suburbs. In the 1970s, political unrest in Africa and the Middle East brought even more diverse Muslims into the city.

Today, over one million Canadians are Muslim, making Islam the second largest religion in the country. In Toronto, Muslims account for almost 8% of the population, far outpacing the national average. Learn more about their indelible footprint at the Aga Khan Museum and the Toronto Islamic Center.

Explore one of the world's most diverse cities in Toronto's ethnic neighborhoods—like Greektown, Koreatown, Portugal Village, Little India, and Little Malta—or by visiting museums such as the Reuben & Helene Dennis Museum or the Ukrainian Museum of Canada.

As you consider ways to engage with a full spectrum of identities and experiences, check out resources from the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History & Culture, and Facing History and Ourselves.